Nextflow vs Snakemake

Introduction

Throughout my career, I have always enjoyed the development of pipelines as a mean to efficiently process hundreds of files efficiently. I usually do this directly on Bash, as these pipelines connect the inputs and outputs of different software. I have been able to publish some of these tools in several journals, and at this point I’m always wondering whether they will work in all environments for all users. Although I have made a conscious effort to make them reproducible, they still fail at some point. Another issue is with Bash pipelines, is that I always have to make blocks of “if-else” statements just to check whether the inputs and outputs were created, which is very cumbersome.

During the last 2 years, I have come across Nextflow and Snakemake, which both seem to have the aim to provide an infrastructure for “reproducible and scalable” workflows. In early 2023 I started using Snakemake, and in practice it effectively seemed to provide a cleaner and more organized way to develop and run pipelines. In particular, if you need to run different tools that need their own Conda environment, with Snakemake you can seamlessly define such environments and it will automatically switch them accordingly at execution time. This, however, also seems to be one of its drawbacks as it needs Conda to do so, and this can take ages some times (the always there “Solving environment”.. Just type “conda so” in Google and you will see that the most searched phrase is related to this). Though there is a way to make it run with Mamba, which is faster, it can get confusing if you haven’t worked with Python and Conda environments before. On the other hand, Nextflow, as we will see later, seems simpler, and it doesn’t require jumping into the whole snakes universe of Conda-Mamba-Snakemake.

To get more familiarized with both Nextflow and Snakemake, I adapted a simplified version of my RNA-Seq workflow from scratch to each of these frameworks. In this post I will be discussing some of my findings and what I would recommend for someone wanting to implement them.

The workflow

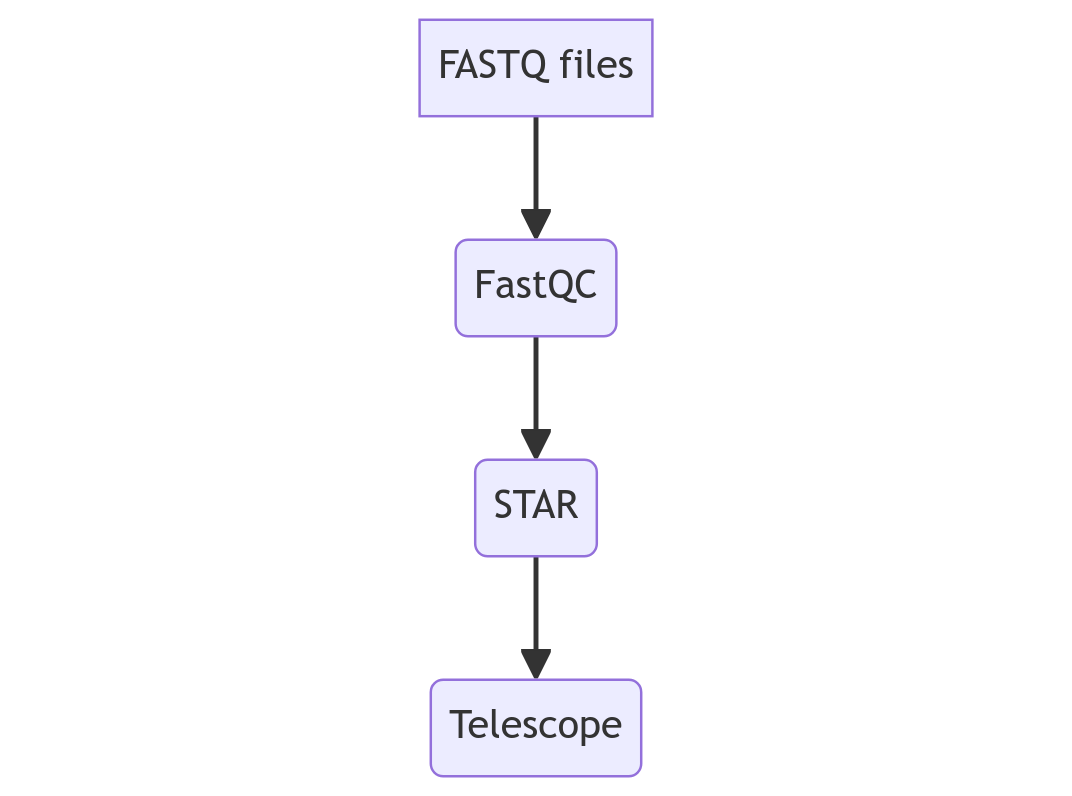

For this workflow, I simulated reads in FASTQ formats: 3 paired-end libraries and 1 single-end library. Then, these reads would need to be quality checked with FastQC, aligned against the human genome with STAR, and finally, processed with Telescope to get expression estimates for Transposable Elements:

There are 2 considerations for the pipeline:

- It should automatically detect whether the libraries are single-end or paired-end.

- Telescope needs to be run on its own Conda environment (I have already built it), so it should be able to reuse the same existing environment.

I will show the implementation first on Snakemake and latter on Nextflow.

Snakemake implementation

Setup

The basic commands for installing Snakemake are:

conda install -n base -c conda-forge mamba

mamba create -c conda-forge -c bioconda -n snakemake snakemake

mamba activate snakemake

snakemake --help

So, right off the bat, we already need to have Conda installed, and before installing Snakemake, they recommend to install Mamba using Conda. If you do this, you might lose a good amount of time. I recommend installing Mamba or Micromamba following their instructions. In my case, I chose to do this with Micromamba, which I started using thanks to a good friend. This is how the commands look:

"${SHELL}" <(curl -L micro.mamba.pm/install.sh)

micromamba create -c conda-forge -c bioconda -n snakemake snakemake

micromamba activate snakemake

Writing the workflow

First, we will define paths to the FastQC and STAR binaries and other parameters:

params_fastqc = "Snakemake_Nextflow/FastQC/fastqc"

params_fastqc_memory = "10000"

params_fastqc_threads = 1

params_star_index = "STAR_GenomeIndex/hg38_STAR_2.7.11b"

params_star = "STAR_2.7.11b/Linux_x86_64/STAR"

params_star_threads = 21

params_telescope_gtf = "hg38_all.gtf"

Next, we will set some variables to guide the different steps of the pipeline. Snakemake allows the use of Python commands, so I’m taking advantage of this. First, the “glob” library is imported, and the “samples” variable is created by listing all files with extension “fq”. Concurrently, through the use of a regular expression, we substitute the trailing _1 or _2 of the paired-end files. In the regular expression we add the quantifier “{0,1}” which makes it also match single-end files that just end on “.fq”, without a trailing _1 or _2.

import glob

samples = list(set([re.sub("(_[12]){0,1}.fq","",x) for x in glob.glob("*.fq")]))

# ['hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10']

Similarly, the “fastq_basenames” variable is created:

fastq_basenames = [re.sub(".fq","",x) for x in glob.glob("*.fq")]

# ['hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10_1', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10_2', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10_2', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10_2', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10_1', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10_1']

The variables “pe_samples” and “se_samples” follow a similar logic, with the exception that the first one will only contain the samples that are paired-end and the second one the ones that are single-end. These variables are used in the function “input_fastqs” which will process a Snakemake input and identify which type is the sample.

pe_samples = list(set([re.sub("(_[12]){0,1}.fq","",x) for x in glob.glob("*_[12].fq")]))

# ['hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10', 'hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10']

se_samples = [re.sub(".fq","",x) for x in glob.glob("*.fq") if re.search("[^_12].fq",x)]

# ['hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE']

def input_fastqs(wildcards):

print(wildcards.sample)

if wildcards.sample in se_samples:

return(f'{wildcards.sample}.fq')

if wildcards.sample in pe_samples:

return([f'{wildcards.sample}_1.fq',f'{wildcards.sample}_2.fq'])

Now we can get to the nitty-gritty. The Snakemake logic is that we define rules with inputs and outputs, and it automatically identifies which rule generates the required input of another rule. For example, it is common to create the rule “all” specifying the final outputs of a pipeline. In our case, it looks like this:

rule all:

input: expand("snakemake_telescope/{sample}_telescope-telescope_report.tsv",sample=samples)

“samples” is our variable defined above. With “expand” we are telling Snakemake to create a list containing filenames of the form “snakemake_telescope/{sample}_telescope-telescope_report.tsv” where sample can be “hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE” or “hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10”. Since those do not exist at the beginning of the pipeline, it will identify the rule that creates those files as outputs. In our case, this is the rule “telescope”:

rule telescope:

input: "snakemake_star/{sample}Aligned.out.bam"

output: "snakemake_telescope/{sample}_telescope-telescope_report.tsv"

conda: "telescope_env"

shell: "telescope assign --outdir snakemake_telescope --exp_tag {wildcards.sample}_telescope {input} {params_telescope_gtf}"

As we see, its output are in similar definition to the outputs of our rule “all”. The complete workflow definition is:

rule all:

input: expand("snakemake_telescope/{sample}_telescope-telescope_report.tsv",sample=samples)

rule readqc:

input: expand("{fastq_base}.fq",fastq_base=fastq_basenames)

output: expand("snakemake_fastqc/{fastq_base}_fastqc.html",fastq_base=fastq_basenames)

shell: "{params_fastqc} --memory {params_fastqc_memory} --threads {params_fastqc_threads} --outdir snakemake_fastqc {input}"

rule map:

input: input_fastqs

output: "snakemake_star/{sample}Aligned.out.bam"

shell: "{params_star} --genomeDir {params_star_index} --runThreadN {params_star_threads} --readFilesIn {input} --outFileNamePrefix snakemake_star/{wildcards.sample} --outFilterMultimapNmax 100 --winAnchorMultimapNmax 100 --outSAMtype BAM Unsorted"

rule telescope:

input: "snakemake_star/{sample}Aligned.out.bam"

output: "snakemake_telescope/{sample}_telescope-telescope_report.tsv"

conda: "telescope_env"

shell: "telescope assign --outdir snakemake_telescope --exp_tag {wildcards.sample}_telescope {input} {params_telescope_gtf}"

As discussed above, rule “all” is the main rule defining the final outputs, which are generated by “telescope”, which in turn requires BAM files generated by the “map” rule. Snakemake has the option “–dag”, which allows us to get a quick overview of the rule graph:

It shows us that we have 4 samples processed by the “map” rule, and this goes to “telescope” and finally to “all”. Having this dependency between rules is what makes Snakemake a good option for developing pipelines: if the files are not generated, it will report an error, which we can debug. In contrast, doing this via Bash will entail several conditionals to ensure we are not overwriting successful runs and that we are properly handling interprocess dependencies. When I used Bash, I would end up creating random empty files because one process wouldn’t finish properly, and then the next one would start anyway.

We can run the entire workflow like this:

snakemake --snakefile RNASeq_workflow.smk --cores 1 all readqc --use-conda

Both the “all” and the “readqc” rule are defined as targets, because we are not actually connecting anything with the FastQC outputs. This is why it appears without connections in the graph. Although we can make it connected to the mapping process, there is not an actual dependency in terms of inputs and outputs.

Nextflow implementation

Setup

In the Nextflow homepage it says that it requires “Zero config” and “Just download and play with it. No installation is required”. It requires Java, but other than that it can be set up with:

curl -s https://get.nextflow.io | bash

This doesn’t take more than 2 minutes, and indeed it requires zero installation. It creates a “nextflow” binary in the same directory where the command was run.

Writing the workflow

Similar to the Snakemake example, I first set up some variables:

params.fastqc = "Snakemake_Nextflow/FastQC/fastqc"

params.fastqc_memory = "10000"

params.fastqc_threads = 1

params.star_index = "STAR_GenomeIndex/hg38_STAR_2.7.11b"

params.star = "STAR_2.7.11b/Linux_x86_64/STAR"

params.star_threads = 21

params.telescope_gtf = "hg38_all.gtf"

Instead of rules, we have “processes”. The logic in Nextflow is that a process can take an input and generate an output. The inputs and outputs are called “Channels”, and they can be of any type. For example, the “read_qc” process looks like this:

process readqc {

publishDir "nextflow_fastqc"

input: path fastq1_files

output: path "${fastq1_files.baseName}_fastqc.html"

"$params.fastqc --memory $params.fastqc_memory --threads $params.fastqc_threads $fastq1_files"

}

whereas the “align” process is:

process align {

publishDir "nextflow_star"

input: tuple val(basename),file(fastqfiles)

output: path "${basename}Aligned.out.bam"

"$params.star --genomeDir $params.star_index --runThreadN $params.star_threads --readFilesIn $fastqfiles --outFileNamePrefix ${basename} --outFilterMultimapNmax 100 --winAnchorMultimapNmax 100 --outSAMtype BAM Unsorted"

}

and the “telescope” process is:

process telescope {

conda '/home/ws2021/miniconda3/envs/telescope_env'

publishDir "nextflow_telescope"

input: path bam_files

output: val "${bam_files.baseName}_telescope"

"telescope assign --exp_tag ${bam_files.baseName}_telescope $bam_files $params.telescope_gtf"

}

So, for “readqc” the inputs are FASTQ files and the outputs are the generated HTML files, which share the basename of the input FASTQ file. Then, in “align” we take as input a tuple, containing the sample identifier, and the FASTQ files (this way we can use the sample identifier for “outFileNamePrefix”), and the output is a BAM file. For “telescope” the input is the BAM file, but here I defined the output as a simple value.

The workflow can be defined then as follows:

workflow {

PAIRS = Channel.fromFilePairs("*_{1,2}.fq")

SE = Channel.fromPath("*.fq").filter { it.name =~ /[^12].fq/ }

SE2 = SE.map { it -> [it.simpleName,it]}

readqc(Channel.fromPath("*.fq"))|view

align(PAIRS.concat(SE2))|telescope

}

Nextflow seems to have many ways to interact with sequencing data. For example, we can generate two file / path Channels in the first two lines. The first one uses “fromFilePairs” which is perfect for paired-end files. On the second, we use a “fromPath” to consider all files with “.fq” extension, and we filter it to remove those ending with “1” or “2”, effectively keeping single-end files. We process this variable with “map” to tranform it into a tuple:

PAIRS = Channel.fromFilePairs("*_{1,2}.fq")

#[hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10, [hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10_1.fq, Snakemake_Nextflow/hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1100_s10_2.fq]]

#[hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10, [hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10_1.fq, Snakemake_Nextflow/hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m1000_s10_2.fq]]

#[hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10, [hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10_1.fq, Snakemake_Nextflow/hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f20_m900_s10_2.fq]]

SE = Channel.fromPath("*.fq").filter { it.name =~ /[^12].fq/ }

#hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE.fq

SE2 = SE.map { it -> [it.simpleName,it]}

#[hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE, hg38_tes_random_n1000_simulated_pe_reads_l150_f15_SE.fq]

This way, we can create a single variable that will allow for the proper processing of reads whether they are single- or paired-end. Altogether, the workflow definition is:

workflow {

PAIRS = Channel.fromFilePairs("*_{1,2}.fq")

SE = Channel.fromPath("*.fq").filter { it.name =~ /[^12].fq/ }

SE2 = SE.map { it -> [it.simpleName,it]}

readqc(Channel.fromPath("*.fq"))|view

align(PAIRS.concat(SE2))|telescope

}

Something that I really liked is the ability to pipe processes. Since “align” emits the BAM files required for “telescope”, we can just link them with the pipe.

The Nextflow workflow can then be run with:

./nextflow RNASeq_workflow.nf -with-conda

Comparison

First things first, I have to say that I enjoyed using both Nextflow and Snakemake, and I wish I would’ve started using them sooner, as they are really convenient. Here, I adapted a really simplified version of what I usually do for RNA-Seq analysis so I could get an understanding on how each framework could be used and implemented. Also, it allowed me to make an unbiased and informed opinion on each one. For example, I didn’t have a very good opinion of Snakemake because according to my previous supervisor, it wasn’t able to use already existing Conda environments. Now I know better because I started to use it properly by carefully reading the documentation, the same way I do with any new thing that I start to learn.

If you only plan to analyze sequencing data, I would probably recommend Nextflow because it has built-in features that enhance compatibility and handling this type of data. Setting Nextflow up has to be one of the fastest and hassle-free things that I have done. On the other hand, if you are not familiar with Java, you might face some issues in terms of syntax and how you can manipulate variables. I’m of the idea that once you know how to code in one language, switching to a new one can be fast. Still, I haven’t used Java in years, so I’m a bit rusty. Luckily, they provide documentation to Groovy, the specific name of the language, which helped me during this comparison. By contrast, in Snakemake you can use Python (which I learned over a year ago), and thus, for the functionalities that were missing I was able to quickly write some code to aid in the pipeline, as shown above.

Another misconception that I had was the incompatibility of Nextflow with Conda environments. Nextflow allows for the seamless use and deploying of Conda environments, so if you are familiar with them, you are not really required to use Snakemake.

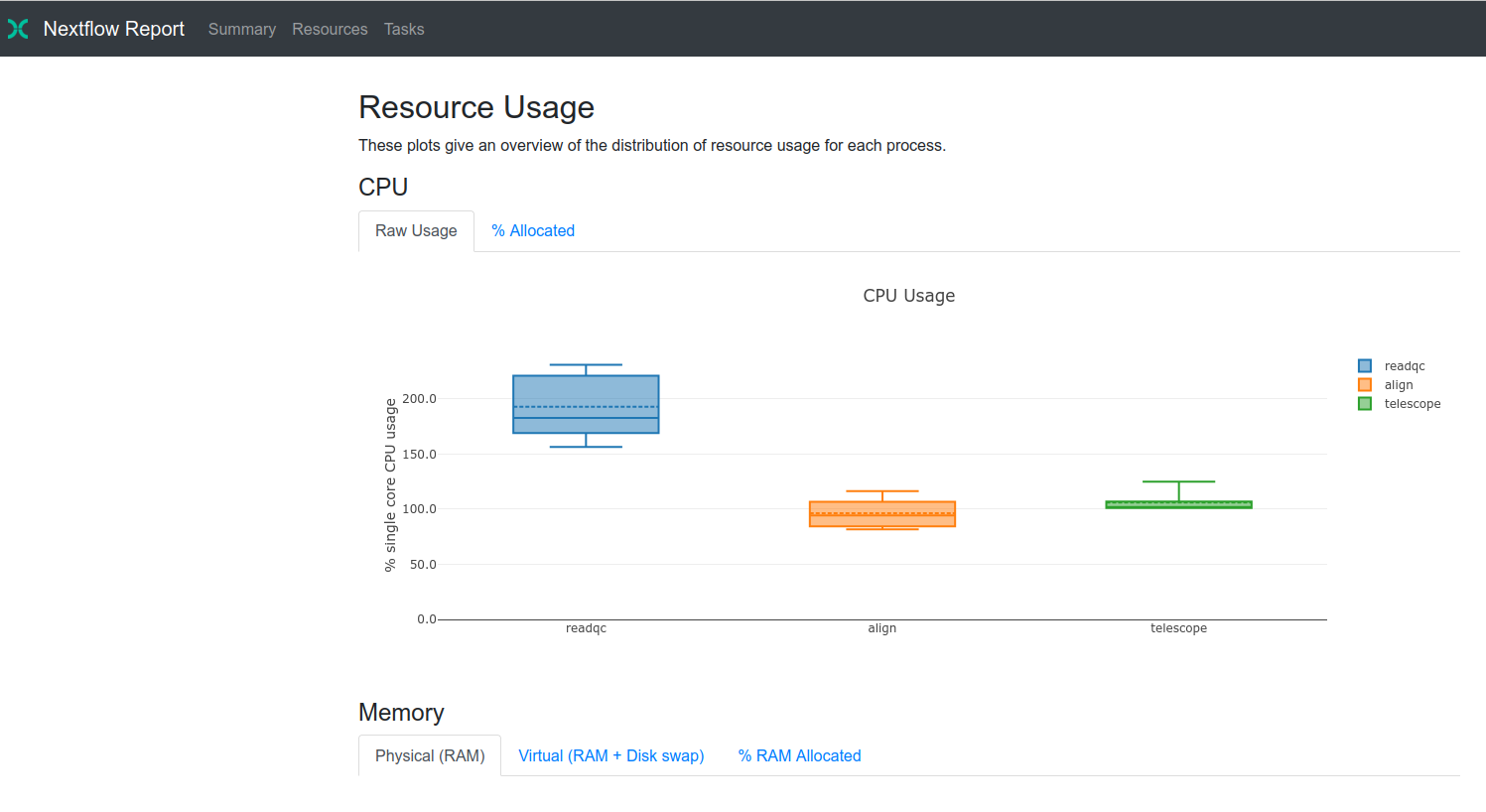

Probably where Nextflow has the edge is in terms of scalability, outputs and reports. For scalability, its ease of use can be very convenient if you work in a cloud-computing environment or in a computer where you have limited capabilities to install software, such as Conda. I didn’t test it here, but I’m curious of their performance in AWS, for example. In terms of outputs, when you run the pipeline by default, Nextflow only shows the process and the completion percentage. On the other hand, Snakemake prints all the standard output of each rule, so you will see a similar output several times for each file processed in a rule, which will result in a messy terminal. Finally, Nextflow creates a beautiful and comprehensive report by just adding the -with-report OUTPUT_HTML option. You can see the report for this workflow here.

With this report you can quickly get an overview of several metrics of importance, such as CPU and memory usage per process and task, and as well as job duration. This can quickly help identify which processes are causing bottlenecks in the pipeline and if a process failed, whether it was caused by a mismatch in allocated memory and peak memory and so on. Overall, this report will go a long way in providing you with the detailed information that will help improve your pipelines.

Summary

Here is a short summary of this comparison:

I think that both frameworks are excellent and I recommend everyone to give them a try (or at least to one of them). However, given Nextflow’s ease of installation / minimum requirements, the ability to generate amazing reports with just a flag, and more compatibility straight out of the box with sequencing data, it will be my default recommendation in the meantime.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: